Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheardAre sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on

– John Keats, ‘Ode to a Grecian Urn’

Back when I was in my late teenage phase of lexical obsession, I used to memorise every single polysyllabic word I’d come across, so much so my ambition at one point was to become a walking thesaurus. For real.

With each new vocabulary I was able to deploy in daily patois (ahem, they say old habits die hard), I’d feel a surge of self-assurance and superiority. But worry not, the rest of the blog post isn’t going to be in this kind of register, because I’ve long outgrown that sort of insecurity. It’s interesting though, to think how appending a few more syllables to words could possess the power to inflate one’s ego.

Among my trove of ego-boosting gems, there was one I particularly liked – ‘epiphany’. While this word originally carried biblical connotations, meaning “insight through divine inspiration”, over the years it has gradually shed its theological plumage and taken on a more philosophical connotation, referring to “a sudden realisation or a great revelation”. I first came across it when reading literary criticism on James Joyce’s short story ‘The Dead’, in which the protagonist Gabriel ultimately comes to a tragic epiphany about the passionless nature of his marriage.

I was reminded of this word, however, because I recently came to an epiphany about this blog.

And this epiphany is what I’d like to talk about in today’s post.

How it all began

When I started this blog about 3 years ago, I actually thought of it as a continuation of my dissertation paper, in which I tried to find the meaning and purpose of literary criticism.

Essentially, I was writing lit crit about why people bother writing lit crit, not because I was convinced that pulling an academic meta-gimmick would bag me a First, but rather, I wanted to understand why creative work needs critical analysis in the first place.

Why can’t we just leave novels and poems alone, and let people enjoy and make of them what they will? Why propose interpretations and influence others with your take on what a given work is about? Heck, why do English professors – who basically make a living out of writing literary analysis – even exist?

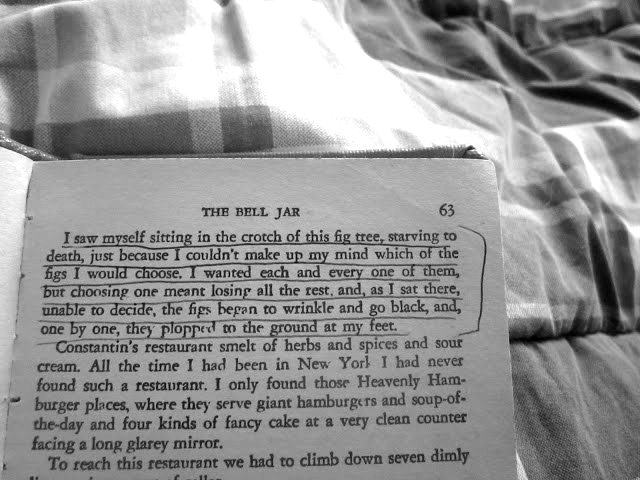

Well, I ended up with the tentative conclusion that, perhaps, just perhaps, the act of analysing literature is, in fact, also a creative act, if not even more so, because reading generates not just one, but multiple, understandings of a single work. A neo-Bluestocking English Professor’s A feminist discourse on ‘The Bell Jar’ does not have to be any less creative than Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, and the imagination of authors is not mutually exclusive to the interpretation of critics.

In fact, the best literary critics are often those who interpret imaginatively. Reading what they think of literature is like reading a creative essay that expands the parameters of your understanding; you may laugh at the ludicrousness of how far-fetched their analysis of a given symbol in a novel is, or you may scorn at the frivolity of how serious they take the use of run-on lines in a poem to be, but one thing’s for sure: good literary criticism always invites some kind of emotional response from the interested reader, but the best literary criticism invites emotional response from the layman reader who may not even be interested in literature in the first place.

So?

So… I set up this blog because I wanted to write what I believe to be the ‘best’ kind of literary criticism, and to do so outside the proverbial ‘Ivory Tower’ of academia, preferring instead the public domain of social media. This is because I resisted – and continue to resist – the idea that literature is a coterie pastime, accessible only to an exclusive, ‘elite’ bunch who have had the fortune of being well-educated. The perpetuation of this myth has got to be one of the greatest ironies of all time, seeing as literature is nothing if not a compendium of all human experiences and emotions.

And thinking deeply about how a given poem, novel, or play portrays humans and humanity from different angles, how they apply to our own lives and invite us to reflect on the way we live, is an exercise in improving self-awareness, and in my opinion, one of the best approaches to living a more conscious, meaningful life.

As time went by, I realised that I would use this blog to share snippets of my personal life, which I’d always relate to something I was reading at that given point in time. While this isn’t a problem per se, I began to notice how I was increasingly unable to share as much about work and life on here as I’d like to, because the blog is a public platform, not a private journal. I’d end up self-censoring out of privacy concerns, or sometimes just straight up not write a post because I’d self-censor so much that by the time I was done there wasn’t much point left to it all.

Most importantly, I came to the epiphany that I’ve slowly but surely moved away from my original intention for Classic Jenisms, which is to focus on the joys of conscious reading and of literary appreciation, not on myself. I came to realise that I had started turning this blog into a solipsistic outlet, where I’d share whatever whenever I felt like sharing. Again, not a problem in and of itself, but not quite what I initially had in mind for this blog.

Next steps?

Of course, change is the only constant, and it’s only natural for ideas to evolve over time. But with the advent of both the Gregorian and the Chinese New Year, I had a thorough think about where I’d like to take this blog going forward, and I’ve decided to start a separate but related project.

The aim of this project is simple, and a return to the roots of this blog – to make literary criticism meaningful and accessible for as many people as possible. I’ll be working on it under the radar for the time being, and I anticipate that it’ll take at least a few months before I can bring it to light.

It may work, or it may not, but I hereby pledge my word that I will give it my best shot, and that you’ll be the first to know about it here once I’m ready to launch it.

* * *

All this, because I truly, madly, deeply believe that literary criticism / creative interpretation / imaginative reading / conscious reading / appreciative analysis / however you want to call the act of creating meaning from poems, books, and plays, is one of the few things that make life a more rewarding experience.

Because it stems from love.

Pure, unadulterated love for the portrayal of what it means to be human.

Recently, I came across the website of an independent second-hand English bookseller called ‘

Recently, I came across the website of an independent second-hand English bookseller called ‘