Thus were my sympathies enlarged, and thus

Daily the common range of visible things

Grew dear to me– William Wordsworth, ‘The Prelude: Book 2’ (1789)

“How are you a better person for having read this book?”

So asked my colleague to a student last week.

The book referred to is Roald Dahl’s Danny the Champion of the World. In response, I think the kid mumbled something about being braver, just like how the protagonist Danny rescues his dad from a pit-trap all by himself.

I don’t think the kid half-arsed his answer; I think he genuinely believed in what he was saying. I, for one, also wanted to believe in the kid; hand on heart, I truly did.

I still do.

This is Danny. Every boy wants to be like Danny.

But for what my cynical two cents are worth, I suspect that Dahl’s book didn’t actually make him a better person. At least not in the sense of the book having left a lasting impact on the student’s character. To be honest, I don’t think most books have the capacity to do that – to effect immediate character growth as if the process is as straightforward as flicking a light switch.

It begs the question, then, as to whether any novel or book can ever truly – lastingly – shape any reader into a ‘better person’.

What does being a ‘better’ person even mean?

Drawing on the past decade of my life, I think the point at which I began to mature – to become mentally and emotionally ‘better’, so to speak – was when I started taking an interest in classics. I don’t mean ‘Classics’ in the ancient Greek and Latin sense, or even Shakespeare or anything written before the 19th century or the Victorian age. A safe inaugural point would probably be 1821, the year in which Gustave Flaubert and Fyodor Dostoevsky – two of my first literary loves, were born.

Flaubert (left) and Dostoevsky (right)

I can still recall the dazed feeling after finishing Crime and Punishment in the summer of Year 9, mainly because I couldn’t understand how Raskolnikov, the protagonist who murdered his landlady in a fit of rage, was able to inspire such sympathy in me as a reader. For all of Raskolnikov’s moral failings, I found myself rooting for him all through the book, which concludes with Sonya, Raskolnikov’s lover and a ‘hooker with a heart of gold’, accompanying him to Siberia for eight years of penal servitude and spiritual redemption.

Note the tape on the edges – a testament to how sacred I held this book to be at the time

The same thing happened when I read Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, to which I was initially drawn, subsequently repelled, and ultimately won over by the adulterous protagonist Emma. At 15 years old, I don’t think my black-and-white self really understood why a woman, despite being in a stable and loving marriage, would want so badly to saddle off with emotionally stunted dickheads like Leon and Rodolph to be in self-destructive affairs, but for some reason, I never once felt like Emma was doing anything wrong, even when my personal values didn’t align with hers.

Children’s literature v. Classic literature: Which one is ‘better’ for you?

The cases of Raskolnikov and Emma are interesting, especially in light of the question that opens this post. In the gamut of children’s literature, the argument for moral instructivism and characters-as-role models usually holds, since children’s books tend to double up as ‘conduct manuals’, offering cookie cutter aphorisms on the Good, the Bad, the Right, the Wrong (and the Very Bad That Will Happen To You If You Ever Get It Wrong).

Harry Potter, for instance, isn’t just about the incredible imagination that gave us Bertie Botts Every Flavour Beans and Quidditch, but also the importance of sticking by your mates through thick and thin, of knowing that while “Books! And Cleverness!” are great stuff, “there are more important things – friendship and bravery”, as the brainy Granger puts it.

Nor is Charlie and the Chocolate Factory all about getting you to fall in love with the coco(a) or the hilarious Oompa-Loompa song that has terribly fat midgets lecturing you on the ills of getting, eh, “terribly fat”, but about the parabolic message of ‘poor man triumphing over rich man’, the consequences of being a glutton and the rewards of humility.

This is all clear enough, and the fact that these works spell out what they want to convey is, I suppose, a major reason behind their widespread appeal.

But what about literary classics, which are more often than not stories centred on less-than-pleasant, unattractive, weird, confused, complicated, morally questionable, or just straight-up repulsive people?

If learning by example is anything to go by, then surely these books can’t claim to instruct readers on being ‘better’ people or living the ‘good life’:

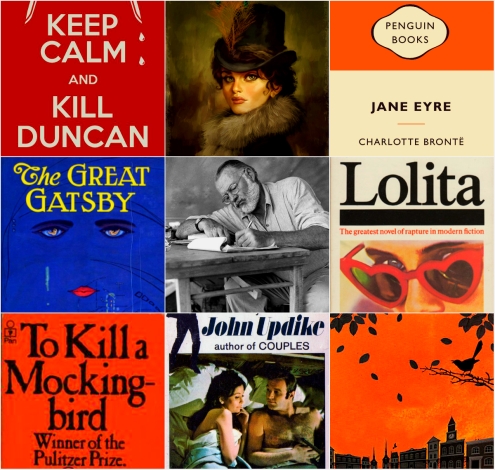

From Shakespeare’s Macbeth (murderer) to Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina (adulterer) to Bronte’s Rochester (wife-abandoner and suspected bigamist) to Joyce’s Bloom (poo-obsessed pervert) to Fitzgerald’s Gatsby (delusional profligate) to Hemingway’s Jake Barnes (homophobe) to Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert (paedophile) to Updike’s Rabbit Angstrom (serial cheater and misogynist) down to Harper Lee’s Atticus Finch (once minister of justice to wronged African-American man in To Kill a Mockingbird, now outed racist in Go Set a Watchman), it seems that no one – high or low, black or white, young or old – is exempt from the literary ‘curse’ of being flawed, of being all too human.

All morally questionable works?

These aren’t characters anyone would aspire to become, but they are, in fact, closer to ourselves than we’d like to admit, as they amplify the parts in us which we consciously ignore and conceal from others. Such cracks and crevasses in our character are the equivalent of sewage pipes in a palace: hidden underneath a polished facade, but no less existent in the very edifice on which the façade depends.

And yet, by being the most honest version of our many alter egos, these human dummies hold up the best mirror for us to scrutinise our faults as we would those of others, to examine ourselves from a comfortable but honest remove, and to look deeper into our true nature through the judicial lens of a reader.

Never thought I’d say this, but I owe a lot of who I am today to paedophiles, womanisers and alcoholics.

Hmm.

Barnes asks: Can we become ‘better’ people by reading more novels?

Incidentally, I came across a related question while reading Julian Barnes’s The Sense of an Ending (2011), in which the narrator, Tony Webster, lives through adolescence, adulthood and retirement only to find himself grappling with the same question for over half a century:

Does character develop over time?

As a cocksure, philosophic 16-year old at boarding school, Tony once feared that –

Life wouldn’t turn out to be like Literature. Look at our parents – were they the stuff of Literature? At best, they might aspire to the condition of onlookers and bystanders, part of a social backdrop against which real, true, important things could happen… Real literature was about psychological, emotional and social truth as demonstrated by the actions and reflections of its protagonists; the novel was about character developed over time.

But when the precocious youth quizzes (somewhat nosily) his friend Adrian on the latter’s turbulent, “novel-worthy” family history, he is disappointed to learn that people in real life don’t exactly undergo the same growth curve as characters do in novels:

“Why did your mom leave your dad, [Adrian]?”

“I’m not sure.”

“Did your mum have another bloke?” (He’s thinking of Anna Karenina here)

“Was your father a cuckold?” (Othello, obviously)

“Did your dad have a mistress?” (Too many examples but Rabbit, Run is the first one that comes to mind)

“I don’t know. They said I’d understand when I was older.” […]

“Maybe your mom has a young lover?” (Definitely Madame Bovary, or maybe Lady Chatterley’s Lover…)*

“How would I know. We never meet [in her house]. She always comes up to London.”

This was hopeless. In a novel, Adrian wouldn’t just have accepted things as they were put to him. What was the point of having a situation worthy of fiction if the protagonist didn’t behave as he would have done in a book? Adrian should have gone snooping, or saved up his pocket money and employed a private detective; [or] gone off on a Quest to Discover the Truth. Or would that have been less like literature and too much like a kids’ story?

(p.16-17, Vintage edition)

*All comments in parentheses mine

Even at sixteen, Tony suspected that there may have been more than a tinge of naiveté in his understanding of human character. Fast forward to 50 years (and 100 pages) later, he revisits the perennial question that has bothered him for so long:

Does character develop over time? In novels, of course it does: otherwise there wouldn’t be much of a story. But in life? I sometimes wonder.

(p.103)

The distinction Tony makes between ‘literature’ and ‘kids’ story’ is apt: reading about characters in “Real Lit” is usually less satisfying than reading about those in Kiddie Lit. But the kind of “novels” he’s talking about here as a 60-year old retiree is actually not the “Real Literature” his 16-year old self was referring to – the “George Orwell and Aldous Huxley” that he used to love and read.

The distinction Tony makes between ‘literature’ and ‘kids’ story’ is apt: reading about characters in “Real Lit” is usually less satisfying than reading about those in Kiddie Lit. But the kind of “novels” he’s talking about here as a 60-year old retiree is actually not the “Real Literature” his 16-year old self was referring to – the “George Orwell and Aldous Huxley” that he used to love and read.

Instead, this sort of novel is closer to popular fiction, more specifically, bestseller paperbacks written with the commercial imperative of appealing to “story”-hungry readers, and by authors who would forgo psychological honesty (e.g. Adrian’s ‘I don’t know/I’m not sure’) for any crude or contrived character ‘shift’.

Literature, however, is nuanced and complex like life, in that there are usually no rational answers to irrational, spur of the moment actions that people often come to regret long after doing them but keep doing them anyway. This is why, at 60 years of age, Tony Webster finally realises that people are –

just stuck with what we’ve got. We are on our own. If so, that would explain a lot of lives… and also – if this isn’t too grand a word – our tragedy.

Lahiri answers (or does she?)

Reading Lahiri on a rainy day

Still, it’s unfair of me to tar all ‘bestseller paperbacks’ with the same brush, if not because I’ve recently read one that I’m almost certain will become canonised as a 21st century classic in the future – Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Lowland (2013).

I say this because one of its protagonists, Gauri Mitra, is afflicted with the same literary ‘seal of authentication’ for being deeply flawed and powerfully alluring because of her flaws. After losing her husband Udayan to the Naxalbari peasant killings in 1970s Calcutta, Gauri agrees to marry Udayan’s Rhode Island-based brother, Subhash, out of desperation, believing that by leaving India she can realise for herself and her daughter a new life in the States.

And yet (spoiler alert!), the Land of the Free delivers neither freedom nor happiness to the woman, and even with Subhash’s love and adoration, Gauri cannot bring herself to fill the traditional shoes of a wife-and-mother stereotype, preferring instead to pursue a ‘life of the mind’ by becoming a philosophy professor.

As such, she makes the unthinkable leap after being given a job offer by a college in Claremont: geographically, she moves from East to West – Calcutta to Rhode Island to California; personally, she transitions from forced domesticity to self-imposed solitude – wife to mother to singlehood and childlessness.

And so, in the tenth year of her daughter’s life, Gauri, in an act that will scar the family for the rest of their lives, leaves Subhash and Bela behind and cut off all contact from them.

‘Robin’s Nest’, by Christine Bray

But here’s the irony:

In the classroom [at Claremont] she led groups of ten or twelve, introducing them to the great books of philosophy, to the unanswerable questions, to centuries of contention and debate. She taught a survey of political philosophy, a course on metaphysics, a senior seminar on the hermeneutics of time. She had established her areas of specialisation, German Idealism and the philosophy of the Frankfurt School.

She broke her larger classes into discussion groups, sometimes inviting small batches of students to her apartment, making tea for them on Sunday afternoons. During office hours she spoke to them in her book-lined office in the soft light of a lamp she’d brought from home. She listened to them confess that they were not able to hand in a paper because of a personal crisis that was overwhelming their lives. If needed, she handed them a tissue from the box she kept in her drawer, telling them not to worry, to file for an incomplete, telling them that she understood.

The obligation to be open to others, to forge these alliances, had initially been an unexpected strain… [but] over time these temporary relationships came to fill a certain space. Her colleagues welcomed her. Her students admired her, were loyal. For three or four months they depended on her, they accompanied her, they grew fond of her, and then they went away. She came to miss the measured contact, once the classes ended. She became an alternate guardian to a few.

(p.282, Vintage edition)

Instead of being the rightful, permanent guardian to one – her daughter, Gauri chooses to be “an alternate guardian” to a few who come and go and visit and leave in seasonal cycles.

Is Gauri’s decision irresponsible or courageous, immature or feministic?

Is she wrong for abandoning her daughter, and is she right for going after her goals?

If she didn’t leave her family behind in Rhode Island, would she be more appealing or boring of a character?

Does preferring “temporary relationships” to an umbilical bond make you less of an ideal mother, but more of your own person?

After reading Lahiri’s novel, do I aspire to become a better mother, or am I inspired to go down the ‘strong-independent-woman-at-all-costs’ route?

Had I been in her position, would I have done the same?

While these are questions which may seem to invite polarising responses, I think my truth is closer to this:

I don’t know.

I’m not sure.

And this, I suspect, may be the one response that ‘real’, timeless literature hopes to get from all of its readers.

Because it is the only one that can set literature free.

Just like Gauri.

‘Mother Bird and Mother Bird’, by Lucho Trejo, Acrylic on canvas

Hello Jennifer,

Good that you have discovered Jhumpa Lahiri – by no means an airport pulp fiction writer and I agree, based only on her short stories that I have read, that hse is destined to be regarded in the future as a canonical writer. You must check out ‘A Temporary Matter’ by her.

David Johncock

LikeLike

Hi Mr Johncock,

Thanks for checking out my blog! Will definitely look up your suggestion. In fact, her ‘Namesake’ is next up on my reading list!

Otherwise, hope all’s well!

Best,

Jennifer

LikeLike

… and on the same subject, John Carey’s ‘What Good Are The Arts?’ is pretty much required reading.

LikeLike

Could not agree more! Carey was my professor’s mentor, and apparently quite a maverick persona back in his heady Oxford days…

LikeLike

I believe reading broadens our perspective, often on things we would subjectively see as wrong. It allows us to relate more, even if through fictional characters. We find parts of ourselves that we may be ashamed or embarrassed about in these characters. I guess it all depends on your definition of better. I think the more relatable, understating, non judgemental, empathetic we are, the better we are. So yea, I think reading more books can make you a better person.

LikeLike

Definitely agree with your point about embarrassing traits of ourselves being played out in fictional characters. How ’empathetic’ we as readers can become, though, is a question open to debate… Thanks for reading! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! Ur blog is wonderful nd has rich content 🙂 keep up the good work.

Btw, my frnd nd I hv jst started a blog . Please do check it out 😀

LikeLike

Thanks Nandika and Tanishka! That’s a great blog name you guys have there 🙂 Glad you enjoyed my blog. I’ll be sure to keep myself updated with your upcoming reviews!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks a lot! We are more than happy that many people including you like our blog and we really enjoyed your blog 😀

LikeLike

Hey 🙂

I just discovered your blog and I am so impressed by your articles! This one about reading and if it makes you a better person is so amazing! 😀

Maybe you want to take a look at my blog too?

LikeLike

Thank you so much! Keep loving books and I look forward to reading more of your posts soon x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! 😀 That’s great!

LikeLike

Brilliantly put!! Such a great blog! This is surely going to be my philosophical fix for the day ! Love and good vibes your way ♡♡♡

LikeLike

Thank you so much! Your words mean a lot to me 🙂

LikeLike

Fantastic, thought provoking piece. Loved your analysis of Lahiri’s The Lowlands.

LikeLike

Thank you so much! Glad you enjoyed it and do stay tuned for me posts 🙂

LikeLike

Great piece.

I just had this discussion with my cousin, a screenwriter, yesterday. I am writing my second novel and one of my first draft readers has told me that she would like my character to go through more ‘change’, to ‘take control’, rather than ‘having life happen to her’. I am grappling with this, as it is a little unrealistic based on her background and circumstances… especially with regard to her faith… yet I know she is right.

Equally, on the idea that novels can change a reader for the good – I am not sure either. I have been told by readers that my first book made them think, raised awareness about a hitherto unknown part of the world (Tajikistan) and about women’s rights. It made them feel grateful, and I suppose, even if only for as long as they remember it, did them some good…

I will follow as I really enjoyed this post.

LikeLike

Thank you so much! I would love to read your novels – what’s your first book called? On inspiring change in readers, I do believe that even the smallest thought-provoking remark in a book makes a difference. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure. I look forward to your next post! My book is called ‘The Disobedient Wife’, by Annika Milisic-Stanley. On my blog, I have various reviews and info about it. Nice to connect 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well done….. 👍🏻☺️I loved reading what u wrote…. Pls read my posts also . I am new here and have written only 2articles

LikeLike

Thanks! Sure, will check out your posts 🙂

LikeLike

👍🏻

LikeLike

Fascinating blog, very elegantly written and presented and full of richness 🙂 Many thanks.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for reading! Much appreciated 🙂

LikeLike

I find it interesting that most of the really serious reading I do (as opposed to reading that passes the time) is for this very reason: to become a better person. If I’m reading your blog correctly, most people who read ‘seriously’ think of betterment the way I do, which really means that it gives them a better sense of themself as a person. And most likely, it gives them a sense of other people as people.

Whilst I can’t speak for HK, most of us reading in Western cultures do so in an environment that values the self and personal freedom above all other things, and in which I consider myself and my needs as both more important and more real than other people’s. I don’t think it’s too much to suggest that most of us who are reading to ‘better’ ourselves are doing so as a way of overcoming this inherently selfish kind of thinking, and as a way of connecting with something outside our solipsistic thinking. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the writers I connect most with are the writers who challenge me to think outside of the beliefs and opinions I already believe.

I’d be interested to know if this rings any bells with your other readers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I definitely agree with you on that the writers I’m most drawn to are those who often create characters radically different from myself, be it in terms of values, beliefs or behaviour. You could say it’s the theory of ‘opposites attract’ being played out in reading, or a perverse fascination with the ‘Other’ on my part, but ultimately I think it all boils down to our desire to define who we are – precisely by looking at what we are not. By eliminating the traits that we (consciously) deem unsavoury or unidentifiable, it seems that the contours of our ‘Self’ would come all the more to the fore.

The beauty of ‘serious’ reading though, is in its bringing us to the realisation that who we are inevitably includes aspects of who we do not want to be. This then draws us closer to these apparently ‘radically different’ characters, and as such cinches a humanistic bond between the fictional being, the readers and the author.

For me, this is the process that brings about maturity and growth.

Thank you so much for reading, by the way, and I hope you stay tuned for more! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a wonderful post. Thank you so much for writing it. I love reading and always felt that to some degree reading broadened my mindset.

But that hasn’t made me a “better person” and life has certainly challenged my ability to stick to my own values.

I plan to read The Lowland, it sounds like something I could relate to. And yet, I know I could never leave my children. I’m really interested to find out why Gauri had to leave her daughter behind completely. Or why she felt she had to. I suspect this is where I would differ from her.

The question of preffering temporary relationships over long term ones is very interesting also. There needs to be more open conversation about how challenging long term relationships can be vs the immediate gratification you experience with someone new. And this is relevant for all sorts of relationships, not just romantic ones. I can see myself posting about this in the future.

Thanks again. I love your work. Lauren x

LikeLike

Thank you so much Lauren! Your words mean a lot to a budding writer like me 🙂

Regarding Gauri’s decision to leave her family – the rational part of me is quick to believe I’d never do something like that, but then again we’re all capable of surprising ourselves. Although I do wonder how I’ll respond to Lahiri’s novel in 20 years’ time, when I will have effectively ‘become’ a different woman with a whole range of new experiences under my belt.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope so…

LikeLike